Barryville New York located in Western Sullivan County, situated on the historic Delaware River. In its prime, the Upper Delaware River area was a mecca for retreating from city life. John F. Kennedy, Bette Davis, Charles Lindburgh and Paul Newman are but a few of the celebrities who have been to our area. Today, the area is experiencing a proud and swift resurgence of popularity. The intrigue of yesteryear is back!

A Driving/Walking Tour of Historic Barryville

In 1844, the Sullivan County Board of Supervisors briefly considered moving the county seat from Monticello to Barryville, at the time a thriving community of about 300 on the D&H Canal. The supervisors eventually decided against the move, and while it is interesting to speculate how such a change might have impacted the history of the area, many Barryville residents have come to understand that what they have is something that no Board of Supervisors, no legislature, no congress, could ever designate. They have the Delaware River and all the accompanying beauty nature has provided. And with the recent designation of Route 97 as a Scenic Byway, many others are finally realizing that nature has bestowed an unrivaled magnificence and majesty to the surrounding landscape.

But there is much more to Barryville these days than natural beauty. Not that the natural beauty has diminished. On many a day, particularly in the winter months, one can spot bald eagles in the stand of trees that line the river’s banks. There are waterfalls and rock formations. There are also shops and restaurants and antique stores. A recently formed Chamber of Commerce has begun taking an active role in enhancing the perception of a main street business district. And the remnants of the industries around which the tiny community grew in the 19th century make interesting viewing. This combination driving and walking tour will help you do just that while acquainting you with the remarkable history of the area.

What's in a Name

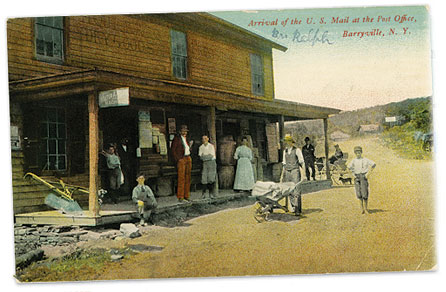

Barryville is named for William T. Barry, postmaster general under President Andrew Jackson. The community grew up around the D&H Canal, which opened in 1828 and operated until 1898. The canal ran through what is today the center of the hamlet, and the canal company operated a number of stores, an office and a dry dock there.

The Delaware River also served as the conduit for timber cut in the area and rafted to Philadelphia for use in the ship building industry. Men made fortunes in the timber business, and when the industry died in the middle of the 19th century, many river communities died with it. In fact, writing in 1899, John Willard Johnston, lawyer, historian, and the town of Highland’s first supervisor, predicted a dire future for Barryville.

"Barryville is a small, poor village now," he wrote, "but at one time supported an active business. The lumber of the region being exhausted, the business of canaling declining and now abandoned, it has for the last 25 years been waning, until now it seems to have reached a bottom of hardpan. Human imagination can hardly reach anything in the future likely to improve it; but it will probably remain indefinitely the small poor place it now is."

Striving to Revitalize

One can only wonder what Johnston would say if he could see his old hometown today. Though it is somewhat spread out, and there are no sidewalks, much of Barryville, especially the section along River Road, can best be seen on foot.

One can only wonder what Johnston would say if he could see his old hometown today. Though it is somewhat spread out, and there are no sidewalks, much of Barryville, especially the section along River Road, can best be seen on foot.

Download the "Historic Walking / Driving Tour of Barryville, NY" >>

But let’s start our tour in the car, heading south on Route 55 from Eldred. This winding road will take you along Halfway Brook, named by early pioneers because it empties into the Delaware River roughly halfway between where the Ten Mile River and the Mongaup River enter. You’ll pass by the county highway facility, the Highland Transfer Station, and the former Tallwood Lodge, once one of the area’s premier resorts, and now the Veritas Therapeutic Community. As you approach the intersection of Routes 55 and 97, you will note on your left a powerful waterfall, which once powered a factory that etched fine glassware for Libbey and other manufacturers. The foundation of the building is still visible just below the falls. Still closer to the intersection, and across the small bridge that spans the brook, is the old Barryville school house, which today serves the Town of Highland as night court and polling place. It was built in 1867 and is one of the oldest buildings in the area. High up on the mountain behind the school house is what used to be known as Fish Cabin Falls, and this remains quite a sight, especially after a heavy rain or during the spring thaw.

The intersection of Route 55 and 97, marked by a blinking light, has long been considered the heart of Barryville. Directly in front of you as you sit at the intersection is the soon to be replaced bridge to Shohola, Pennsylvania. This bridge opened in 1941 and succeeded the suspension bridge upriver. You’ll also note, just to the left of the bridge, the Carriage House restaurant, a nostalgic, if not historic, place once operated as Clouse’s and then later, and for many years, as the renown Reber’s Restaurant and Motel.

You’re going to turn right at the blinking light and travel north on Route 97, now the Upper Delaware Scenic Byway. Much of Route 97 is built on the remains of the D&H Canal, constructed to take coal from the Moosic Mountains of Pennsylvania to New York City via the Hudson River. In fact, stone walls are still visible on both side of the road for the next four miles (all the way to the famed Delaware Aqueduct or Roebling Bridge, which carried the canal across the Delaware). This stone work is quite distinctive, and you will definitely know it when you see it. The canal was the economic lifeline for Sullivan County in its earliest days, and it is one of our most important and successful historic preservation efforts.

Drive about four tenths of a mile north on Route 97, passing, among other landmarks, the newly renovated River Market, formerly Eckhart’s, and more recently Oelker’s Store, Tre Alberi Restaurant, and the eclectic Barryville Emporium, to the Spring House Commons, which is on your left. Pull into the parking lot here and begin the walking part of our tour.

The Spring House was opened as a boarding house by George Layman in 1899, and offered its guests "an excellent water front, well shaded lawns, and everything conducive to (their) health and comfort." It was purchased by a small group of transplanted New Yorkers a few years ago and thoroughly restored and rebuilt to house a number of unique shops offering such sundry items as antiques, fine coffees, art, and pet supplies.

The parking lot accesses the back of the Spring House, but you’ll want to walk around to the front, which will provide a great look at the wood framed Victorian structure with the expanse of porch so typical of a Sullivan County Silver Age resort. The building faces River Road, which parallels the Delaware, and will serve as the initial stage of our walking tour.

If you stand on River Road, facing the Delaware, with the Spring House at your back, you will see on the opposite bank of the river the tracks built by the Erie Railroad in 1848 and still used by freight trains today. The Shohola (Pa.) Depot also served Barryville, and the two communities were linked first by a crude rope tow ferry and later by a suspension bridge, both of which we’ll discuss in a moment. If you’re fortunate, you may also see a bald eagle or two.

If you venture to your right, upriver, you will pass by the house that served as the home of Shelley Winters and Pruitt Taylor Vince in the 1995 indie film, Heavy, which was shot largely in Barryville and nearby Highland Lake. It’s the last house on the road, and has been thoroughly restored since the movie was made. Immediately next to the house is the property of another old resort, the Riverside Cottage, which thrived during the 1940s, ‘50s and ‘60s. The rambling buildings have now been removed, but the remains of the swimming pool serve as a lonely testament to another era.

Back in the opposite direction, the history lesson continues. Just past the Spring House, you’ll notice a large stone abutment on the river bank, and a matching one on the Pennsylvania side. This stone work anchored the suspension bridge originally built by local contractor Chauncey Thomas in 1856. Legend has it that Thomas wanted to hire suspension bridge expert John A. Roebling to build the structure, but Roebling was otherwise engaged, and couldn’t fit the Barryville project into his schedule, so Thomas built the bridge himself with just a few hand-written notes he obtained from Roebling as his guide. The bridge was sorely needed to connect Barryville and the D&H Canal to Shohola and the Erie Railroad, and it immediately hosted a steady stream of traffic. It wasn’t much of a bridge, though, and flipped over in a wind storm in 1859. The bridge was destroyed, with only the piers and abutments surviving. It was promptly rebuilt, and operated without incident until 1865, when a cable snapped under a heavy load. When the bridge reopened in 1866, it had a center pier, and was much improved. It served the two river communities until the present day bridge was completed down river in 1941. The large green home across River Road from the abutment was built by Stephen St. John Gardner, who served as president of the bridge company after Chauncey Thomas.

As you proceed along River Road, you will no doubt notice a laid up stone dyke protecting the road from the river. This dyke was constructed by the state in 1904, after a series of destructive floods, and has prevented considerable damage to homes along this stretch of river over the years since.

The Barryville Methodist Church will come into view momentarily. It is one of two churches that once stood on River Road. The Baptist Church was just two doors down. As you continue along River Road, you will pass by the site of the old ferry that originally linked Barryville and Shohola. This ferry, no remnant of which exists today, was pressed into service each time the old suspension bridge was damaged and had to be rebuilt.

Farther down River Road is Until Next Time, a delightful antique store that was formerly Frank’s Luncheonette. At the store, you’re going to turn left, up Mail Road, but before you do, you’ll see still farther down River Road the remains of Clouse’s Casino and the old Riviera movie theater, once the lively gathering spot for locals and visitors from miles around. Just across from that is the bustling construction site for the new bridge.

Walk the short distance up Mail Road to Route 97. Up on the hill to your right is the old Congregational Church, now a private residence. The small cemetery behind the church is the burial ground of two Confederate soldiers, brothers John and Michael Johnson, killed in the infamous Great Shohola train wreck of July 15, 1864.

A train carrying 833 Confederate prisoners of war and 128 union guards on their way to Elmira collided with a coal train on a blind curve just north of Shohola, killing at least 51 Confederate soldiers and 17 guards. Five Confederate prisoners escaped in the chaos. The dead were buried in a mass grave along the tracks, while over 100 injured soldiers were taken to Shohola and Barryville for treatment. Many of them died from their wounds, and two of them, the Johnson brothers, were buried in Barryville. The soldiers buried along the tracks remained there until 1911, when they were disinterred and removed to Elmira’s Woodlawn National Cemetery, where a single stone monument is engraved with the names of the known dead, Union names facing north and Confederate names facing south.

At the southwest corner of Mail Road and Route 97 is a great place to examine canal remains, especially in the winter and early spring, before the foliage covers it. Then, make a left and walk north on Route 97, back to the Spring House and your car.

From here, you will want to continue north on 97 for four miles to the Roebling Bridge. This four mile stretch will feature a number of sections of well-preserved canal remains, including a wonderfully restored section sponsored by the National Park Service. You will also pass by a river fishing access, and a bald eagle viewing area.

The Roebling, of course, is one of the most awe inspiring engineering marvels in the area. Designed and built in 1848 by the man who later designed the Brooklyn Bridge, this aqueduct was one of the keys to the financial success of the D&H Canal. It is among the oldest surviving wire rope suspension structures in the world, and is definitely worth examining. There is a convenient parking area just off Route 97, which also provides access to the Zane Grey Museum, housed in the former home of the famed sports and western novelist across the river in Lackawaxen.

You are now just a short drive from the Minisink Battlefield, which is operated by Sullivan County during the summer months. The Battle of Minisink was one of the bloodiest battles of the American Revolution and led George Washington to dispatch General John Sullivan, for whom the county was later named, to drive the Mohawk Chief and British Army Colonel Joseph Brant from the area.

On the 20th day of July in 1779, Brant led a raiding party of Indians and Tories against the settlement at Minisink, near present day Port Jervis. Brant, an astute and adroit military tactician, had learned that a Colonial Army detachment under Count Pulaski, which had been assigned to defend the sparse settlements in the Mamakating, Neversink, and Delaware Valleys, had been re-deployed elsewhere, leaving the area largely unprotected.

Brant’s objective was to gather livestock, produce, and whatever other provisions he could find and stockpile them in order to help the British and their Mohawk allies camped out in the Susquehanna Valley survive the following winter. If he could devastate and demoralize the settlers and distract the Colonials from their fight with the regular British Army, all the better.

Having completed the raid, plundering and burning homes, killing the men, and dispersing the women and children, Brant and his men took their bounty and returned northward, along the Delaware, on their way back to the Susquehanna. Word of the raiding party shortly reached Goshen, where the call went out for the militia to gather under the leadership of a local -physician, Colonel Benjamin Tusten.

After hotly deliberating the merits of engaging the marauders in combat, Tusten and 149 men - merchants, farmers and clerks and what James Eldridge Quinlan later described as "some of the principal gentlemen of the county" - set out the next day in pursuit of their quarry.

"Colonel Tusten was opposed to risking an encounter with the subtle Mohawk chief with so feeble a command," Quinlan wrote, "especially as the enemy was known to be greatly superior to them in numbers. The Americans were not well provided with arms and ammunition, and it was wise to wait for reinforcements. Others, however, were for immediate pursuit. They held the Indians in contempt, insisted that they would not fight, and declared that a recapture of the plunder was an easy achievement. The excited militia men took up their line of march, and followed the old Kathegton (Cochecton) trail seventeen miles, when they encamped at Skinner’s mill, near Haggie’s Pond, about three miles from the mouth of Halfway Brook. This day’s march must have nearly exhausted the little army. How many men of Orange and Sullivan, in these effeminate days, can endure such a tramp, encumbered with guns and knapsacks?"

The following morning, July 22, 1779, Tusten and his men - bolstered by a contingent from Warwick under the command of Colonel John Hathorn, finally confronted Brant on the banks of the Delaware just above present day Barryville. Almost immediately, Brant deftly cut the militia’s force in two and an epic battle ensued on a hilltop overlooking the river. Ammunition was soon depleted, and the combat was reduced to hand to hand, with the Mohawks and Tories getting much the better of it. The militia was routed, and nearly all of those who stayed and fought, including Tusten, who had set up a crude field hospital under a large outcropping of rock, were killed. What became of those militia who were cut off from the fray was not recorded.

"We do not believe that the annals of modern times contain the record of a more heroic defense, " Quinlan wrote. "In vain, for hours Brant sought to break through the cordon of patriots. The devoted militia men repelled him at every point. What the fity were doing wwho were in the morning separated from their companiomns we cannot learn. They may have been driven away by superior numbers and they may have been blustering cowards, brave in council, but timid in real danger. Their movements are veiled in oblivion, and there we must let them remain."

Following the bloody day long battle, Brant and his remaining men forded the river and continued on their journey. They somehow managed to avoid the severe retribution for their actions administered a few weeks later by General John Sullivan and his army of 3,000, who swept through Wawarsing, Mamakating and Deerpark, through Easton and Tioga Point, and destroyed anything Iroquois they encountered along the way.

The remains of those slain on that desolate Barryville hilltop in what forever after would be known as the Battle of Minisink, were not afforded a proper burial. Quinlan wrote that "for forty-three years the bones of those who had been slain on the banks of the Delaware were permitted to molder on the battle ground. But one attempt had been made to gather them, and that was by the widows of the slaughtered men, of whom there were thirty-three in the Presbyterian congregation of Goshen. They set out for the place of battle on horseback, but finding the journey too hazardous, they hired a man to perform the pious duty, who proved unfaithful and never returned."

Finally, in 1822, "a committee was appointed to collect the remains and to ascertain the names of the fallen. The committee proceeded to the battle ground, a distance of forty-six miles from Goshen, and viewed some of the frightful elevations and descents over which the militia had passed when pursuing the red marauders. The place where the conflict occurred, and the region for several miles around, were carefully examined and the relics of the honored dead gathered with pious care. The remains were taken to Goshen, where they were buried in the presence of 15,000 persons."

A monument was erected to mark the mass grave, upon which was inscribed the names of the 44 men killed in the battle. Unfortunately, as meticulous as the search for remains had been, only 300 bones were recovered, far fewer than had been expected. Nature and the denizens of the forest had no doubt disposed of the rest. This sad occurrence moved the Monticello poet, Alfred B. Street, to write in the final stanza of his ten stanza commemorative of the battle:

"Years have pass’d by, the merry beeHums round the laurel flowers,

The mock-bird pours its melody

Amid the forest bowers;

A skull is at my feet, though now

The wild rose wreathes its bony brow,

Relic of other hours,

It bids the wandering pilgrim think

Of those who died at Minisink."

The battlefield is truly a sacred spot, and provides a solemn and fitting end to our historic tour of Barryville.